Stories untold: Carbondale woman chronicles Southern Illinois’ black Civil War soldiers

By Gabriel Neely-Streit — February 7, 2019

Corene McDaniel, of Carbondale, checks her research on black Civil War soldiers buried at Mound City National Cemetery. (Gabriel Neely-Streit, The Southern)

For 50 years, Corene McDaniel has walked through the rows of graves at Mound City National Cemetery to visit her father, who lies in rest there alongside thousands of other veterans.

But it was only a few years ago that she noticed an abbreviation chiseled into some of the oldest white headstones: USCT.

It stands for United States Colored Troops, she learned — the name given to about 200,000 black men who fought for the Union in the Civil War.

Representing some 10 percent of the entire Union Army, and 25 percent of its Navy, the men played an instrumental role in preserving our nation’s unity and cementing the freedom promised to them by the Emancipation Proclamation.

However, McDaniel discovered, very little is known about the USCT servicemen buried at Mound City.

“We know they’re here, but not necessarily where they are, or how many,” McDaniel said. She spoke to Mound City Cemetery representative Alex Kment, who contacted the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs in Washington, D.C.

“They said the best way to start was to walk and document,” McDaniel said.

In the last year, McDaniel, walking alone or with friends and family, has identified 350 USCT graves.

“It’s an experience that gives you goosebumps,” McDaniel said. “It is so wonderful to walk here peacefully and know that all of these soldiers have served this country.”

She’s got all the soldiers’ names written in a pocket-sized pink-and-blue notebook, plus the numbers on their headstones, which indicate their location in the cemetery.

“Felix Mattingly, 4497; Thomas Richardson, 4498; Calee Prewitt, 4452; Solomon Brooks, F4465.”

McDaniel, of Carbondale, hopes her records can be added to the directory at the cemetery museum, allowing future visitors to more easily find and visit the USCT graves. That could benefit history buffs, and even families, who frequently visit the cemetery in search of Civil War-veteran relatives, Kment said.

But McDaniel has a second, more ambitious goal. She wants to tell the stories of these soldiers.

“I’m interested in the contribution that was made,” McDaniel said. “There may be so many people that do not know the role they played. In the Civil War we’re thinking about slavery, and not necessarily the sacrifice these soldiers made.”

Their service was indispensable.

“Without the military help of the black freedmen, the war against the South could not have been won,” President Abraham Lincoln said in 1865.

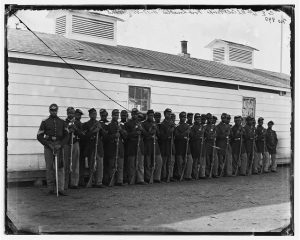

The soldiers of Company E of the 4th U.S. Colored Infantry are pictured at Fort Lincoln, in Maryland. About 200,000 black men served in the Union Army during the Civil War. (Provided by Library of Congress)

Black soldiers were prohibited from joining the Union Army until about a year after the war began, when Congress passed the Militia Act of 1862 recognizing the urgent need for black soldiers.

Freedmen from throughout the North enlisted at a staggering rate, with some even returning to the U.S. from Canada to serve.

USCT recruitment intensified with the Emancipation Proclamation, issued on Jan. 1, 1863. The Proclamation freed slaves in secessionist Southern states and publicly announced that any who so desired would be welcomed into the Union military.

“Make no mistake, the Emancipation Proclamation was aimed at Southern slaves,” said Frank Smith, director of the African American Civil War Memorial and Museum in Washington, D.C. “But it came with an asterisk: you’ve got to put on a uniform and help us to win this war, otherwise this won’t have any meaning.”

During the last two years of the war, from 1863 to 1865, black soldiers “fought in every major campaign and battle,” according to the museum’s website, earning 52 Medals of Honor, and helping to capture major strategic targets like Charleston, South Carolina, and Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy.

Black women, including Harriet Tubman, worked as nurses, spies, and scouts to support the Union cause, although they couldn’t enlist in the military.

Because of the prejudice against them, many black soldiers were withheld from combat and instead were placed in support roles as carpenters, chaplains, cooks, and laborers, according to the National Archives.

Still, nearly 40,000 black soldiers died over the course of the Civil War, and they endured some of the war’s harshest and most dangerous conditions.

They received lower pay, insufficient supplies, and often stronger punishments when captured by the Confederates.

Their segregated regiments also received greatly inferior medical care, with many white physicians unwilling to treat black soldiers and just three black physicians serving the Union Army’s 166 black regiments, according to the news website OZY.

A headstone at Mound City National Cemetery shows the abbreviation U.S.C.T., which stands for United States Colored Troops, the name given to black soldiers who served in the Civil War. (Gabriel Neely-Streit, The Southern)

McDaniel, who comes from a proud military family, said she hadn’t given much thought to the ugly truths her project might uncover in Southern Illinois. But she’s prepared for them.

“What we have is a sign of the times,” McDaniel said. “This is the way it was then, it’s not the way it is now. I’ll be looking for information without being judgmental about what I find. The goal is to be informed and help people be more informed.”

But researching the USCT soldiers at Mound City is going to take determination.

Very few black soldiers originated in Southern Illinois, as the state had just one black regiment, said P. Michael Jones, director of the General John A. Logan Museum in Murphysboro. Both during and after the war, the USCT soldiers who ended up in the region came from far and wide.

Now a town of just a few hundred people, Mound City was then home to a naval shipyard and one of the largest Civil War hospitals, serving thousands of wounded.

“It was one of the most strategically important locations in the Civil War, second only to the capital,” Kment said.

Wounded soldiers were brought to Southern Illinois by ship from all over the south and Midwest, via the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. Those who died in treatment were buried at Mound City, and in many cases, the cemetery has no record of where the soldiers came from.

After the war ended, thousands more soldiers came to Mound City, when the Army undertook a massive project to dig up soldiers lying in battlefield graves and transfer them to newly created national cemeteries like Mound City, Kment said.

That led to another influx of soldiers about whom very little is known, disinterred from makeshift cemeteries near battles at Cairo, Illinois; Belmont, Missouri; and Paducah, Kentucky. Many of them were reburied as unknown soldiers

Still, there are reasons to be hopeful.

The growth of genealogical research and the digitization of government records continue to make it easier to find relevant information.

Jones, the museum director and a former schoolteacher, has profiled almost 40 black veterans who moved to Elkville, De Soto, Murphysboro and other Southern Illinois towns after the Civil War.

He’s used muster rolls and census and pension records to dig up their military histories and a surprising amount of biographical information.

“Particularly in the pension records, there is a wealth of information: where people were born, who they belonged to, when they were enslaved, who they married, who their children were,” Jones said.

While black Illinoisans still faced discrimination and violence after the war, Jones’ research indicates the USCT veterans received special respect.

“They got obituaries in the newspapers, which, back then, were usually reserved for people with some status,” Jones said. “You would see these obituaries mentioning how few old Civil War veterans were left. They may have called them black veterans, but there was respect for those men and what they did.”

The USCT soldiers’ service “changed the image of black people in the world,” Dr. Smith agreed.

But it has often gone undervalued and under-recognized — a historical neglect that, to Smith, exemplifies the unequal treatment black Americans still face today.

Corene McDaniel speaks with Alex Kment, the cemetery representative at Mound City National Cemetery, about her efforts to catalogue black Civil War soldiers buried there. (Gabriel Neely-Streit, The Southern)

McDaniel hopes continued research on the USCT troops buried at Mound City, most of whom died in wartime, will help set the record straight.

And she’s got a long list of interested helpers, from her fellow members of the local Zeta Phi Beta sorority, to area historical societies, to fellow volunteers at the African American Museum of Southern Illinois, which McDaniel co-founded with her husband.

She’s certain the project will continue to grow. After all, you can Google anything these days, she said.

When the weather gets nicer this spring, McDaniel will return to the cemetery to complete her walk and add the last few names to her notebook.

Then she’ll reach out to her volunteers and figure out what’s next.

One thing she’s sure of: She’ll be getting young people involved.

Each year, the African American Museum of Southern Illinois hosts a monthlong youth summer program, taking children on educational trips throughout the region.

In future years, McDaniel hopes to have a new piece of the story to share with the students when she brings them to Mound City.

“I would hope when this is all done that we would have a great story to tell to our kids, grandkids, students, adults, to anybody that wants to listen,” McDaniel said. “And in telling the story there are going to be some things that aren’t so rosy, but that’s life.”

Gabriel Neely-Streit is a reporter for The Southern Illinoisan in Carbondale. He can be reached at gabriel.neely-streit@thesouthern.com or 618-351-5074.

—Stories untold: Carbondale woman chronicles Southern Illinois’ black Civil War soldiers–